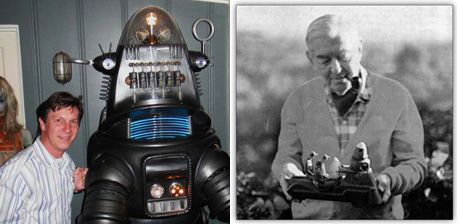

Robert Welch, left with Robby from FORBIDDEN PLANET, and his grandfather, A. Arnold Gillespie, the Wizard of MGM, holding the miniature shuttle driven by Robby.

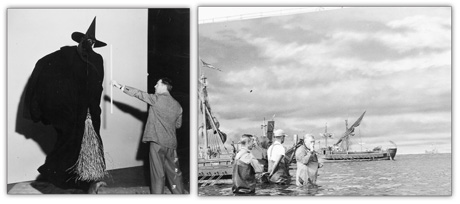

Working on effects for THE WIZARD OF OZ and BEN HUR.

by Greg S. Faller

The complete filmography of Arnold Gillespie is one of the largest in Hollywood, reaching nearly 600 films and almost evenly divided between art direction and special visual effects. He worked on both versions of Ben-Hur and Mutiny on the Bounty, created the visceral quality of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake in San Francisco, the alien beauty of Forbidden Planet, and the maleficent nightmare of The Wizard of Oz. Gillespie’s work in The Wizard of Oz demonstrated the imagination, ingenuity, and patience that became his trademark. To produce the witch’s skywriting of “surrender Dorothy,” he used a mixture of sheep dip and nigrosine dye released through a stylus into milk in a glass tank. The attack of the flying monkeys required the hanging of 2,200 piano wires from the sound stage’s ceiling.

When Gillespie began special effects work for MGM, the studio was an efficient organization, all facets of production departmentalized. He was head of the Special Effects Department under the titular guidance of Cedric Gibbons’ Art Department and in charge of the crews who worked with miniatures, rear-screen projection, and full-scale mechanical effects. The other aspects of visual effects fell under two other main departments; the Optical Department (matte paintings and optical printing) and the Animation Department. Gillespie seemed particularly intrigued with miniatures (Circus Maximus in the original Ben-Hur, the sea battle in the 1959 remake, the tank chase in Comrade X, the ships in Torpedo Run, and the raft sequence in How the West Was Won) and full-scale mechanicals (Robbie the Robot in Forbidden Planet and the four Bountys used for the 1962 version of Mutiny on the Bounty). But his forte lay in designing solutions for odd effects never before photographed. As in the skywriting effect described above, he usually employed liquids in a glass tank. To create the plague of locusts in The Good Earth, Gillespie dumped coffee grounds into a water tank, filmed their dispersal upside-down, and then superimposed the image with shots of the crops. For the atomic explosion in The Beginning of the End, he visualized a mushroom cloud before photographs and information were declassified by the government. By releasing blood bags under water and superimposing the image with a background shot, Gillespie manufactured an effect so believable and accurate that government officials thought he had access to secret materials. The footage was later used by the United States Air Corps in their instructional films.

Gillespie had the talent and a studio system to make the remarkable, the unexperienced, the fantastic, and the cataclysmic very believable and authentic. As he described his profession in a FilmComment interview, “The whole physical end of movies, in my opinion, was so interesting because whether the picture was modern, whether it was in the future, whether it was a dream world like The Wizard of Oz or in Outer Space like Forbidden Planet, it was illusion made real.”